Many discoveries have been made in the history of mankind. The author of the innovation called con-servo was the Frenchman Nicolas Appert, for which he received the title of “Benefactor of the Fatherland” from Napoleon. And Clarence Birdseye is considered the founder of the modern frozen food industry.

Nicolas Appert

Born November 17, 1749 in the town of Chalons-en-Champagne, he was the ninth child in the family of an innkeeper and owner of a small hotel named Francois. Nicolas grew up in the kitchen, surrounded by steaming pots and hot pans, joining the cooking craft. However, other children of Francois were forced to help their father in the kitchen. But only from Nicolas came a deli, besides – a noble one. By the way, his brother – Benjamin Appert was a famous writer and publicist.

Upper Jr. quickly gained popularity among his milieu, and he was invited to cook in rich houses. Gradually, the chef’s fame crossed the borders of France, and when Nicolas turned twenty-three, he went abroad: to the German city of Zweibrücken. Appert became a cook for Duke Christian IV, and after the death of the nobleman, he prepared meals for his widow.

Nicolas returned to his native land after twelve years of absence – in 1784. Having saved some money in a foreign land, he opened a pastry shop and a bakery in Paris on rue des Lombards.

In July 1789, the French Revolution broke out, and Appert, most likely on a denunciation, ended up in prison. The poor fellow could well have been sent to the other world – the death sentences were then passed by the Revolutionary Tribunal incessantly, and the guillotines in the squares worked around the clock. But fate kept Nicolas – three months later he was released as unexpectedly as he was arrested.

Nicolas opened a restaurant on the Champs Elysees. His business went so well that he soon opened a couple more restaurants in the same area. However, he did not stop there. The Frenchman, a naturally inquisitive and inquisitive person, was attracted not only by the culinary arts but also by ways of preserving food.

In the 18th century, in order to protect food from spoilage, it was simply salted, dried or smoked. But these simple ways changed the taste of foods and often not for the better. Appert, on the other hand, wanted to achieve a way in which food would not lose its beneficial properties.

In Nicolas’ “laboratory”, meat, vegetables, and fruits were languishing in giant pans from morning to evening. Then he put the foods in glass jars – Upper ordered from a friend who owned a small glass factory, a batch of vessels with a wider neck.

He hermetically closed them, put them in a separate room and changed the boiling time, timing, storage temperature. And all the data was carefully recorded.

A few months later, Nicolas opened the containers and conducted a tasting. Sometimes he was satisfied with the results of the experiments, sometimes the opened con-servos gave off such a bad smell that they had to be thrown away.

The experiments were long and difficult. Appert spent a lot of energy and lost a lot of money. It would seem that you need to calm your ardor. Moreover, the famous chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac was skeptical about the idea of a restaurateur. “Give up your meaningless occupation,” he said. Everything that is dead must rot.

Another, perhaps, would have left these experiments, but only not the frantic Frenchman who did not leave his “laboratory” for days on end. He possessed truly incredible perseverance.

In 1795, Appert moved to the town of Ivry-sur-Seine, located a few kilometers from the capital. Why did he go there? Perhaps the land was cheaper in those places. Or maybe in the quiet town of Nicolas it was calmer to implement his ideas …

In Ivry-sur-Seine, he opened a trade in canned food. It cannot be said that the novelty was a stunning success – buyers looked at the sealed bottles with bewilderment and were in no hurry to open their wallets. In addition, unfamiliar goods were expensive.

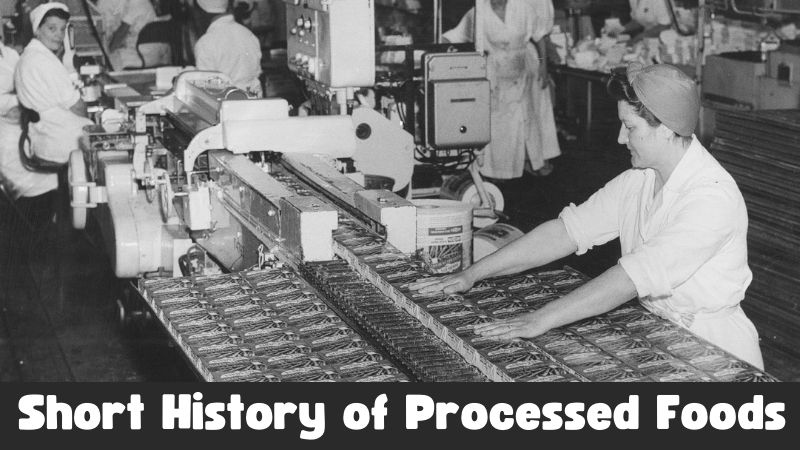

Nevertheless, Nicolas stubbornly moved forward, and in 1802 he created the first con-servo factory in the world. The enterprise, which employed five dozen workers, opened in the southern suburb of Paris – Massy and was called La Maison Appert. Our hero produced canned food in bottles closed with a special clip.

Over time, Nicolas began to place canned food in more durable tin boxes. Of course, Appert’s canned goods were not at all like modern ones. They were heavy iron boxes. An ignorant person could not even assume that there is something edible in their insides.

However, there were difficulties with tin, since it was produced in England. France at that time was at enmity with the island empires, and one day the export of this container stopped. Appert had to go back to glass.

In December 1803, Appert began exporting his products – 60 bottles of canned vegetables were sent to Russia and 55 – to Bavaria.

Soon another significant event took place.

Appert delivered a batch of bottles of soup, beef in sauce, green peas and beans for the first time to the French Navy. By order of the Admiralty, the containers were kept for three months, then they were sent to the port of Brest, where the fleet of the empire was based.

The reviews of the sailors who tasted Appert’s dishes turned out to be beyond praise. The soup and the beef in the sauce were declared fit for consumption. Well, canned beans and green peas looked like they had just been cooked.

Inspired by the success, Upper expands the range. His products appeared in a grocery store in Paris. Nicolas opened a shop on the large, busy rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honor, not far from the Elysee Palace.

In 1806, con-servos were presented at an exhibition of foods of French industry. However, Appert’s invention went largely unnoticed. But the author was not upset at all – he was sure that the future belongs to his offspring. He had a daring idea – he decided to report his discovery to Napoleon himself!

Finally, in 1809 Nicolas obtained an audience with the Emperor of France.

Nicolas arrived at the Elysee Palace loaded with three sealed vessels. In one, there was boiled lamb with buckwheat porridge, in the other – stewed pork, in the third – peach compote. Appert opened the first jar and dumped its contents onto a plate. In front of the emperor and his entourage, he put a piece of lamb into his mouth, chewed it and froze in respectful silence.

Then Napoleon took up the fork. After tasting the treat, he looked inquiringly at Nicolas: they say, ordinary food. But Appert stunned the emperor: “Sir! What you deigned to taste was prepared not today, but six months ago. These are the so-called con-servos.

Bonaparte was incredibly surprised: “Six months ago … Did I hear right?” Appert confirmed, “Yes, sir, that is absolutely true. I dare to assure Your Majesty that con-servos can be stored for longer.

The tasting continued, and Napoleon was imbued with more and more respect for his guest.

The emperor always said: “The army marches while the stomach is full” – and quickly realized the benefits of con-servos: thanks to them, the French troops would not experience problems with provisions. In a fit of emotion, the emperor honored Appert with praise and a firm handshake.

After a visit to the Elysee Palace, Appert rejoiced – the road to glory is open! Soon he turned to the Minister of the Interior of France, Comte de Montalivet, outlining the essence of his invention. He suggested either taking a patent for the production of con-servo, or making the discovery available to everyone. Nicholas chose the second option.

A little later Appert derived considerable benefits from his activities. He received a bonus of 12 thousand francs – at that time it was a staggering amount! In addition, Appert received the title of “Benefactor of the Fatherland” and was awarded the gold medal of the Society for the Promotion of National Industry.

… In June 1812, Napoleon’s troops invaded Russia. In France, many were sure that the emperor’s army was heading for another triumph. But, as it soon became clear, it was moving towards death. Within a few weeks, the half-millionth Napoleonic army began to have supply problems. The offensive developed so rapidly that heavy carts with provisions could not keep up with the vanguard.

Were con-servos in the diet of the conquerors? Historians argue that this type of food was present but – in small quantities: the jars are bulky, and Napoleon’s soldiers already had enough difficulties. They had long, tedious marches, they had to carry guns, ammunition, carry the wounded and sick. By the way, the French and their allies in Russia suffered greatly from food poisoning.

There was no con-servo in the emperor’s convoy either. Perhaps his cook, Dunant, was simply afraid to risk the health of his patron. He would definitely be in trouble if something went wrong with the emperor.

What about Appert? What happened to his business? Some French sources claim that he handed over his business to a certain August Prieur, who for some time produced foods under the Prieur-Appert brand.

Little is known about the last years of the con-servo inventor. Already a deep old man, he returned to Massy, where his rise had once begun. He lived in poverty, huddled in a shack and no one knew that he had once been awarded the praise of Napoleon himself and declared a “Benefactor of the Fatherland.”

On June 1, 1841, the author of the original invention passed away. The body of 91-year-old Nicolas Appert was buried in a mass grave, where the poor fellows, like him, rested…

Appert was forgotten, and for a long time. But in 1857, during the World Industrial Exhibition, they remembered him. The con-servos made by Appert for Napoleon were opened there. Why they were kept closed for so long? God knows. But most importantly, the foods were recognized as completely edible. And this is almost half a century later!

Today, in the hometown of Nicolas Appert, Châlons-en-Champagne, a museum of the inventor has been opened and his bronze bust has been installed. In France, the memory of the famous fellow countryman is reverent, streets in various cities are named after him – there are more than six dozen of them!.

Today, probably, there is no person in the world who has not tasted the invention of Monsieur Appert at least once in his life. Tin and glass jars with foods can be found in any home.

Clarence Birdseye

Birdseye improved the process of freezing fresh food, which led to changes in the food industry. He spied on the old methods of the Eskimos, instantly freezing the fish they caught, which, after thawing (surprisingly!) did not lose its freshness. The inventor quickly realized that his ‘discovery’ could go far, and founded his own company.

Clarence Frank Birdseye II was born December 9, 1886 in Brooklyn, New York, and was the sixth of nine children of Clarence Frank Birdseye I and Ada Jane Underwood. Birdseye II studied briefly at Amherst College. In 1908 he was unable to continue his studies due to financial difficulties.

He subsequently moved west, where he worked for the United States Department of Agriculture (USAD). He was a ‘naturalist’s assistant’ in New Mexico and Arizona, and all that was required of him was to help shoot coyotes. Clarence also worked with the entomologist Willard Van Orsdel King in Montana, where in 1910-1911 he managed to catch several hundred small mammals. At the same time, for his research, King removed ticks from animals, which he called the main cause of the outbreak of typhus in the Rocky Mountains.

From 1912 to 1915, Birdseye stayed in Labrador, where he became seriously interested in the process of preserving food by freezing. The inventor had a particular interest in quick freezing technology. Watching the Inuit, the Canadian Eskimos, Clarence tried himself as a fisherman. At a temperature of -40°C, the caught fish froze almost instantly, and then, when thawed, remained fresh in taste. Birdseye immediately determined that frozen food in New York was inferior in quality to frozen Labrador fish, and realized that the knowledge he had gained would bring him good money.

Conventional freezing methods of the time took place at higher temperatures. The process was much slower, so that the ice crystals managed to germinate enough. Today it is known that the faster the freezing occurs, the smaller the size of the crystals that damage the tissue structure will be. When ‘slowly’ frozen food thaws, cell sap flows out of the tissue damaged by the crystals. Because of this, the product in the cooking process becomes either dry or mushy in consistency. Birdseye’s discovery solved this problem.

In 1922, Clarence experimented with freezing at the Clothel Refrigerating Company, and then opened his own, Birdseye Seafoods Inc., where fish fillets were air-cooled at -43 ° C. In 1924, the company went bankrupt from -for the lack of interest in Birdsay’s products. But he did not despair – and developed a completely new production process, originally designed for commercial success. Fish began to be packed in cardboard boxes and passed between two cooling surfaces under pressure. Thus was born a new company, ‘General Seafood Corporation’, practicing the new Clarence method.

Later, Birdseye patented a new freezer that kept small ice crystals from growing to better preserve cell membranes. By 1927 meat, poultry, fruits and vegetables were added to the product line. In 1929, Clarence sold his patents and company for $22 million, but did not stop developing his freezing technology.

Clarence Birdseye died of a stroke at the Gramercy Park Hotel on October 7, 1956, at the age of 70. His body was cremated and the ashes scattered over the water in Gloucester, Massachusetts.

Category: General

Tags: Clarence Birdseye, Nicolas Appert, Processed Foods